Chronic kidney disease in dogs and cats (I)

A review of all the keys to understand and treat chronic kidney disease in dogs and cats

In this series of publications (three in total) we will review the key aspects of chronic kidney disease in dogs and cats 🐶😽

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) in dogs and cats is defined as:

“Presence of structural and/or functional abnormalities lasting more than 3 months”

These changes are generally irreversible.

It is estimated that the prevalence of CKD in dogs and cats is around 0.5-1% and 1-3%, respectively, mainly affecting geriatric animals.

Although the etiology of CKD remains unknown, multiple studies have shown how normal kidney tissue is progressively replaced by fibrous and inflammatory tissue, resulting in the development of tubulointerstitial nephritis in the vast majority of cases.

Other processes (less frequently) include glomerulonephropathies and amyloidosis.

How to recognize chronic kidney disease in dogs and cats?

The retention and/or loss of certain compounds and elements is the trigger for the clinical manifestations that we usually observe.

Generally, dogs and cats with a history (> 3 months) of CKD present one or more of the following clinical signs at the time of consultation:

Polyuria-polydipsia.

Hyporexia.

Vomiting.

Diarrhea.

Weight loss.

In the physical examination, it is common to detect:

Decreased body condition.

Muscle atrophy.

Halitosis.

Stomatitis associated with uremia (sometimes oral ulcerations).

Unkempt coat.

Decreased renal silhouette on abdominal palpation.

Laboratory abnormalities:

Hematology may reveal the presence of moderate to severe anemia (< 20-15%) of the normocytic-normochromic type.

Biochemistry mainly shows:

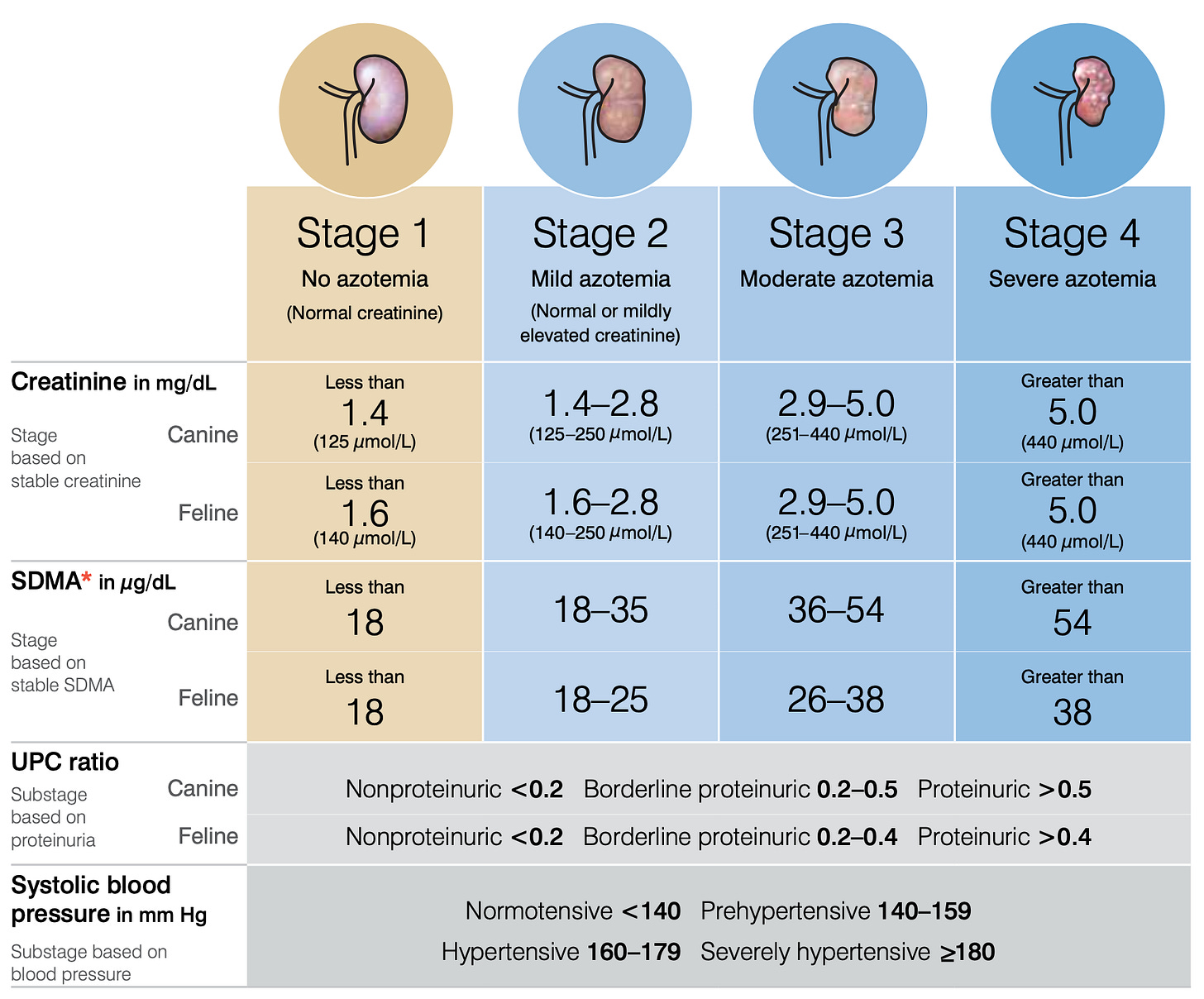

Azotemia (increased creatinine and urea concentration).

Electrolyte imbalances:

Hyperphosphatemia.

Hyper/hypokalemia.

Hypo/hypercalcemia.

Hypoalbuminemia.

Metabolic acidosis.

Measurement of the serum concentration of symmetrical dimethylarginine (SDMA) is particularly interesting in dogs and cats with suspected CKD in the early stages of the disease.

In a recent study carried out in cats with CKD, it was shown that SDMA values increased on average 17 months before creatinine values, allowing earlier recognition of the disease and therefore premature initiation of renoprotective interventions.

Urinalysis can reveal a wide constellation of abnormalities:

Decreased ability to concentrate/dilute urine.

Proteinuria.

Pyuria associated with infection.

Cylindruria.

Hematuria.

Inappropriate pH.

Inappropriate glucosuria.

Cystinuria.

Review of chronic kidney disease in dogs and cats using “Therapeutic Keys”

When addressing the management of a dog or cat with suspected CKD, it is essential to determine an accurate diagnosis of the disease, as well as perform a complete staging.

In order to adequately assess serum creatinine and SDMA concentrations, it is essential that the animal is correctly hydrated at the time of the analysis.

In dogs and cats with suspected proteinuria of renal origin, we must rule out the presence of pre- and post-renal diseases before proceeding to quantify them.

To minimize intra- and inter-day variability in the amount of protein eliminated in urine, we will take urine samples from 3 consecutive days (free catch sample) and perform the measurement on a “pooled sample” (combining equal volumes of all three samples).

Evaluate systemic blood pressure using Doppler or oscillometric methods.

From: http://www.iris-kidney.com/guidelines/staging.html

The treatment of CKD in dogs and cats should focus on:

1- Correct the presence of both renal and extra-renal imbalances

2- Delay disease progression

To cover these objectives we can use of a simple but useful mnemonic rule: NEPHRONS

In the second part (for Premium subscribers) we will address how, by using this mnemonic term, we can cover all the fundamental aspects of the disease 🙂

If this post has been helpful please spread the word with your friends 🔊

Thank you for being part of VETPILL 😊

- Carlos Martinez